We featured this interview on July 1st, 2020 before John Lewis passed. Dawn Porter won Mind the Gap (California Film Institute and Mill Valley Film Festival) Documentarian of the Year on 11/25/20.

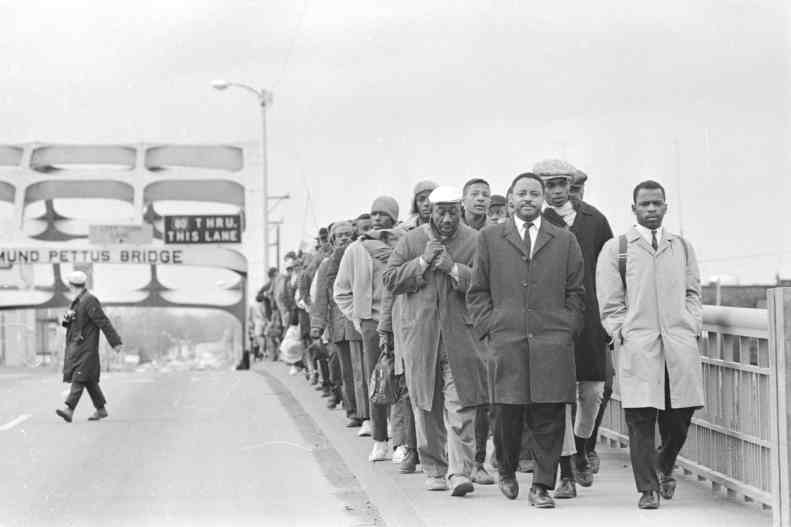

Black Lives Matter. There is a man named John Lewis, who has fought for that for over 60 years, and is still fighting for that in a way that creates results. Everyone, and I mean EVERYONE, should watch Dawn Porter’s documentary, “John Lewis: Good Trouble” and learn from this man. John Lewis started out as an activist in the 1960s leading Non-Violent Protests through sit-ins, freedom rides and walking side-by-side with Martin Luther King Jr. across Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge. He has been beaten, he has been verbally abused, he’s been thrown in jail, and his response takes the form of peaceful protesting. Then he went on to become an impactful congressmen in 1987, and he continues to serve in that role to this day.

The legacy that John Lewis has built is impacting the younger generations by showing what peaceful protesting and good government looks like. Through John Lewis’ story, we can see that it’s possible to reach across the aisle and make REAL change. Some of the younger members of congress that Lewis has taken under his wing include Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ayanna Pressley, Antonio Delgado, and Cory Booker, all of whom give me hope for this government. And that is why we must come back to what John Lewis almost lost his life for many times: the right to vote.

I was honored to talk to Dawn about how she came to this doc following the completion of her “Bobby Kennedy for President” Netflix series, the achievements of John Lewis as both an activist and a congressman, and the legacy she hopes to leave through her filmmaking. “John Lewis: Good Trouble” will be available on demand and in select theaters starting on Friday, July 3rd.

REBECCA MARTIN: What brought you to this project?

DAWN PORTER: I had just finished a series for Netflix called “Bobby Kennedy for President”, and I was still mulling over these questions of how you make social change. I was also really thinking about what it was like during that era. How did we accomplish so much during that time period? John Lewis was in the Bobby Kennedy series, he worked for Bobby Kennedy. Lewis set up the rally for the Black community in Indianapolis, and the rally was supposed to take place on the day that Martin Luther King Jr. was killed. Many of Kennedy’s aids said, “This is too dangerous, you should not speak to this audience.” And John Lewis said, “You should absolutely speak to them. They’re going to be upset, and they need to hear from you.” Bobby Kennedy spoke that day and he gave what some people consider his best speech. It’s one of the only times where he had spoken about his brother being murdered. And Indianapolis was a city that did not have rioting and looting that night.

Their relationship was really interesting to me, as was how they both approached change–Kennedy from within the government and Lewis outside of it. So when CNN came to me and asked if I’d be interested in doing a documentary on John Lewis, I just jumped at the chance to continue thinking about those ideas. How do you make social change? What is the role of an activist? What does it take to get some real things done? That’s how it started, and we went on from there.

MARTIN: This film is so relevant, all the time, but especially now in light of the Black Lives Matter movement, the protesting, and the upcoming elections. From your point of view, what do you hope people will take the most out of this film, and put into action?

PORTER: Obviously we could not have imagined that this film would strike such a chord in the way it has. For me working on this film has been a very positive experience of history, knowing that there is a long story tradition of protests in this country and that history has been successful. There was meaningful change that was introduced directly as a result of this citizen pressure. As we think now about that similar kind of citizen pressure, I think that it’s important for us to remember that this is not a light thing that we do. This is the most critical important thing we can do. To participate is to make our voices heard, both by protest but also by voting.

When we started out, I wanted people to remember that John Lewis is still a working legislator and is still crafting legislation for social change. But I also wanted to remind people of what it took to assure voting rights, and how those rights are still in danger. I think today, it is absolutely imperative that people think about how they live their lives, and how they can assure that some of the structural barriers to advancement for so many people will fall. Not all of us are going to march in the streets, but there is something that each of us can do.

It’s as small as beginning with yourself. Why do you hold certain attitudes? Do you cross the street when you see a black man coming towards you? Do you get nervous in an elevator? We must really challenge ourselves about how we make stereotypes about African Americans and really think about how we live our lives.

I do think we are seeing how our democracy really needs care. It is a participatory democracy, and if we value that, we must participate. So I hope this film encourages that type of participation, but also reminds us that you do have power as a citizen, you just have to choose to exercise it.

MARTIN: The film was very educational for me. It highlighted things that I feel I’d love to adopt or that our country should adopt in practice, such as the Non-Violent Protest workshops. I was so impressed by John Lewis and how peaceful he was as a protester, even with everything that was coming at him. He did not react in a violent way. I feel I would need a lot of workshops to deal with all of the things that were thrown at John.

PORTER: I’m glad that you brought that up. I was struck the same way by that. We all know how brave John Lewis and the other Civil Rights participants were, but I wanted to highlight that they were also really strategic. They studied and prepared these civil actions, and I think that’s really an important lesson for us. If you want to make lasting change, you need to organize and prepare. I was so moved by what Bernard Lafayette, who is one of John’s contemporaries, says in the movie, “We couldn’t go back, because we had changed.” Studying and really thinking and contemplating about what they believed in changed them. They couldn’t accept segregation anymore. They just couldn’t accept it. There wasn’t a choice for those students. I was really struck by how this was so fundamental to their character. They couldn’t stop breathing nor more than they could stop protesting.

This is what archival footage does for you. You see how resolute the students were. There’s the footage of the students when they’ve all been arrested and the narrator says, “They were given a choice, pay a fine or go to jail. Each of them chose jail.”

Most of us avoid jail at all costs. But what these students did was so powerful, that idea that there was this strength of purpose in the planning. We know that Nashville was integrated as the result of direct student action. They focused on these facets of life that impact everyday people, like where you eat, where you shop, and how you travel. What they were asking for was so modest. They simply wanted to be able to order a hamburger and a coke, or travel by bus.

When you think of it that way, you realize that it was those behaviors that they identified as being fundamental to American society. Because these activities are where people can interact. They knew if they could integrate those places, segregation would fall. And that is exactly what happened.

MARTIN: I was also struck by how John Lewis could reach across the aisle and get things done with the Republican Party. That was shocking to me, and gives me a little hope for our government.

PORTER: If a person is as strong in his convictions as John Lewis, and can reach across the aisle, then I think the rest of us can too. No one can accuse him of being a sell-out, or not being strong enough. When you’re on the outside and asking for change, you see how you can afford to be fixed in your opinion. But when you are a legislator, it’s a different skill set, it’s a different kind of work. Compromise should not be a dirty word if it leads you on the correct path. I think seeing his maturity and how his career evolved over time was really interesting to me. It was interesting to me, as a person on the other side of their career, to explore how people continue to change, evolve and grow? And then in doing so, how do you make room for the next generation? That’s what I see him doing, making that room and creating that space by saying, “This is what we’ve done, this is where we’ve came from.” He makes space for people to do things their way.

I have a lot of respect for him. He reached out to new members of congress like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ayanna Pressley, Antonio Delgado and Cory Booker. He is supporting them not as a photo op, but because he believes in good government. They are our next generation of leaders. We have to tell these stories, and we have to pass down this knowledge. That was really interesting to me. I was a PolySci major. I am interested in the mechanics of things and it helped me understand that.

MARTIN: You’re great at capturing onscreen the legacies of very important people in history. What legacy are you trying to leave through your work?

PORTER: Oh wow. What I’m really trying to do is help fill in some of the details of history, and allow people to think about things that they thought they knew, maybe in a new way. I really am curious about people. I do tend to be of an optimistic faith. I’m curious about what makes a good leader, what pushes somebody to speak up. I’m curious about people that we think we know but there are things in their lives that are so important that we may not realize that those are the things that are pushing and motivating them. My first film was about public defenders, which I think are so misunderstood. I would always ask people, ‘What’s the one job that’s guaranteed in the constitution of the United States?’ The thing that you wave that flag about is the 6th Amendment, the right to a lawyer. And that says something about what we all commonly believe, supposedly is that we don’t lock people up without a fair process. I’ve always been interested in how we live up to and how we go about enacting rules that lead us to the civilization that we want.

I think all of my films are an examination of what it means to be a good citizen, and how to improve life not just for ourselves but for other people. I’m also a big proponent of the small film. I feel like you learn so much by giving people their best opportunity to explain themselves by respecting what they want to say rather than what you want to say. I’m a big believer in that. I hope that people will see that connection in my work, even through the different styles, like archival and vérité. Right now I’m doing a film about Pete Souza, Obama’s White House photographer. It’s very different from other films that I’ve made. I just love that there are so many different ways to come at filmmaking. It’s just this endless opportunity, and I love it.

The below was my tribute discussion with filmmaker Dawn Porter about her scope of work in February 2021.

Pingback: The 50 best films of 2020: Part 2

Pingback: Filmmaker Elizabeth Wolff illuminates the Kathleen Lombardo case in her special “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark” episode – Cinema Femme